‘Nothing of what is called inhuman... is beyond man.’ - Jorge Semprun

‘To designate a hell is not, of course, to tell us anything about how to extract people from that hell, how to moderate hell's flames.’ - Susan Sontag

Photography is premeditated. There is thus a thought process and an intention behind every photograph and taking a photograph always implies the framing of one thing and cutting out of another. Photographs capture moments of action to the fraction of a second and fragment our world into bite-sized segments. In this respect, images of pain, suffering and destruction are among the most morally binding. Questions arise as to how a photographer can stand there, watch and record such horrible atrocities; or whether the images we receive are framed for impact and distort the reality and simplify the complexity of the situation. Viewers of photography are not unaware of the disturbing imagery that floods newspapers, magazines, television sets, photography books and museum walls; and such images of warfare, famine and extreme poverty, many viewers will seldom experience first-hand. This raises questions as to whom the photographs are aimed for and the reasons why they are captured and displayed publicly. What use values do these images of pain and suffering actually have within the larger frame of knowledge that such atrocities continue to occur despite the long history of documenting them?

Part I

Photography has aided in making the world feel increasingly small, where exotic far-away lands and cultures become ever more near and familiar (Sontag 1977; 2003). In this sense photography has been dubbed the democratic enterprise that enables the masses to gain a hold on the means of production. The democratisation of photography has created a situation in which everyone has the opportunity to photograph and be photographed. In addition to this, photography sets itself apart from painting through its ability to transcend representation and forge a new territory, that of actualization. This characteristic of photography has allowed for it to maintain itself at the forefront of documentation, carrying with it the implicit notion of capturing objectivity and truth. This, however, is highly contested and debated. And whether an objective truth or reality really does exist ‘out there’ is fundamental to understanding the role of the photographic enterprise, especially documentary photography and photojournalism. For many post-modern theorists, the conceptualisation of an objective reality is widely agreed to be false and misleading. Thus for photojournalists and documentarians this poses many issues for those dedicated to remaining unbiased and objective throughout the process. For artist Renzo Martens, this is an issue that cannot be bypassed, as he argues that the modes of documentation always mimic modes of oppression (discussion, 29 March 2011). Hence one cannot remove themselves from the essential framework and systems in which they belong, and for those who attempt to escape from it by producing objectivity only further reproduce it through covert means. In this sense, aspects of subjectivity are inevitable and should be utilized and integrated into the documentation process. Linfield furthers this notion by positing that photographs are, ‘objective and subjective, found and made, dead and alive, withholding and revealing’ (2010: 237). Undeniably, photography does possess these incongruous characteristics that appear to bestow it with a magical quality that surpasses what we know as reality. Similarly Sontag (2003) has also come to recognise photography as the objective capturing of reality and the subjective interpretation of the photographer. In this sense, the fluidity of truth and reality becomes fused within the framework of subjectivity; and construction must thus be recognised as manifest within all documentary photography.

This contestation that photographs simultaneously contain objective and subjective information is especially lucrative and allows us, as viewers, to retain the notion of a photograph’s almost supernatural ability to reveal a reality below the perceptible surface, or as Benjamin puts it: ‘makes [us] aware for the first time the optical unconscious, just as psychoanalysis discloses the instinctual unconscious’ (1972; 7). Photography as a revealer of clandestine truths may be more of a sentimental notion, similar to that of Barthes’ almost wishful thinking when viewing his mother’s photograph after her death. However, this enchanting quality or sentimentality of photography appears to be what keeps us entranced by images regardless of our beliefs in a hidden reality. In this regard, Benjamin’s may be an overstatement; there is however, a certain collective consciousness that one can argue has developed throughout the photographic enterprise. This consciousness is the elemental aspect that indeed links together all types of photography; whereby ‘all photographs are in some sense about photography; everything one sees or makes to be seen is both self-referential and an element of the larger world to which the clues are more or less obvious’ (Price 1994; 34). Hence, photography is the communal enterprise of taking pictures and the subsequent use and distribution of them. In this sense all types of photography (journalistic, sports, scientific, etc.) become referred back to one another as aspects of our material culture.

Drawing upon this understanding, we can investigate more thoroughly how the production and use of images, specifically of suffering captured by photographers may relay back within the wider photographic enterprise and within the political and social contexts they emerge from. Ariel Azoulay (2008), whose work centres around the imagery being produced from the Israel-Palestine conflict, proposes the notion of a separate and distinct photographic realm which inhabits its own unique space of political relations ‘that are not mediated exclusively by the ruling power of the state and are not completely subject to the national logic that still overshadows the familiar political arena’ (12). This she terms the civil political space. Hence photography becomes a global community free from the state and within this space dictates its own exceptions. The circulation and distribution of photography does indeed occur outside of the control and power of most governing bodies (Didi-Huberman 2003) and mimics this photographic community external to sovereign command posited by Azoulay.

Reiterating a point from above, the viewer in most instances cannot relate to many of the images of pain and suffering from first-hand experience and frankly may never be able to. And as Sontag points out, this distance between the perceiver and the perceived gives this kind of imagery its surrealist quality. Essentially, all photography maintains a surrealist quality about it, by making foreign objects near and familiar, and conversely by transforming familiar objects into foreign and distant ones (Sontag 1977). Hence in both instances there is a distance that remains intact between the viewer and the subject. This notion of surrealism within photography appears to reoccur particularly within the context of images of pain and suffering as the spatial, temporal and social distances are major factors influencing the way in which we perceive and respond to these images. However, the ability of these images to carry surrealist qualities do not ease the viewing of such distressing images and the distance becomes ever more complex as we invest ourselves in them. We, in this context is a problematic concept, and reoccurs throughout the discussion of photography; particularly within photography that hinges upon a sense of moral responsibility. Who are we who view photography of this kind? Are these photographs made for those of relative privilege living predominantly in politically and economically stable societies where violent atrocities are not common aspects of life? Is this kind of photography a commodity that begs to be bought and sold? And again for what purpose does it serve? What are the limits of this kind of photography? Where can one draw the line between those images of pain and suffering that do indeed serve a ‘greater good’ and those which are simply pornographic, sensationalist and exploitative?

In a comic yet astutely executed scene from the show The Sarah Silverman Program (2007), Sarah is confronted by imagery of suffering whilst watching television. The images are distressing. A child living with leukaemia, struggling to walk, lying in a hospital bed, pale and sickly; along with the plea: ‘These are children that are dying [...] these disturbing images don’t have to be real, you can make them disappear with just a few dollars’. Sarah, disconcerted by this imagery, hurriedly tries to change the channel only to discover that her remote control has failed to work, and is subsequently forced to endure the advertisement ‘for the next 36-hours’. Finally, she realises that the commentator is correct and to help relieve her anxiety, she makes the images disappear by covering the entire television screen with dollar bills; agreeing that indeed, her money has solved the problem. This sketch evidently illustrates the way in which images of pain and suffering are utilised as means of provoking visceral emotions in the viewer, and creating a sense of urgency and necessity. In many cases the photographs exorcise intense reactions that are self-motivated to relieve the anxiety or grief caused by the images. What is also so poignantly portrayed is the capacity one has to simply switch off or look away, or in Sarah’s case to physically obscure the image from view. By looking at photographs we simultaneously maintain the agency simply not to look. In this sense, we possess the ability to increase our distance from the photograph and conceptualise it is as purely surreal. Regardless of our agency, it is maintained that images do have the power to burn into our memories and consciousness and the complication arises when we begin to ask ourselves: what these images demand from us as viewers and subsequently as consumers of pain and suffering? Because as Linfield lays claim, ‘the history of photography also shows just how limited and inadequate such exposure is: seeing does not necessarily translate to believing, caring, or acting. That is the dialectic, and the failure, at the heart of the photograph of suffering’ (2010: 33).

Part II

Photographs are made up of three components, in Barthes’ (2000) terms: the Operator, Spectator, and Spectrum. The operator refers to the photographer, that who manipulates the camera and in some cases the environment or situation in order to capture the desired image. The spectator refers to those who view photographic images, whilst the spectrum is the subject of the photograph, the captured object or people. Barthes’ intention in referring to the subject as the spectrum is in reference to the root word: spectacle. The role of each of these elements are particularly important in understanding the use-value of photographs and also the wider context in which some photographs are taken and circulated over others. The photographer as operator infers a sense of control and manipulation. Operating upon their subjects like a surgeon on a patient. The operator’s only contact with the subject is through the wielding of an apparatus, penetrating them from a distance. This distance between the operator and spectrum is mimicked by the distance, touched upon above, between that of the spectrum and spectator. For the operator, the physical distance can never be overcome, however much one may beg to oppose this through embedded photojournalism or by even removing the otherness of the photographer, in instances where the subjects of photography themselves are given cameras to capture ‘their own reality’. The distance here is inherent in the photographic process and resides within the camera when it is physically placed in between two parties.

Again we return to Martens statement about the inevitability of the reproduction of oppression through the process of documentation. It is indeed problematic for both documentary filmmakers and photojournalists to escape the systems from which they emerge and the normative frameworks with which their work must abide. In particular, within both practices, there is a desire to produce a coherent visual narrative that guides the viewer throughout the images. What is challenging about this is the way in which a narrative becomes imposed upon an event or situation. Inherently within this process one is forced to decide between what information to include and which to exclude. Here the event becomes framed within a structure that is familiar to the filmmaker, journalist, or a larger institutional body that dictates how it becomes framed. Hence the event becomes reproduced within the same means of production that engender certain forms of oppression. Butler (2005) provides some examples of how embedded reporting from the War in Iraq has been confined within the limits of an American ideological perspective. With respect to the images and reporting coming from the frontline, not only has it been dictated what is ‘appropriate’ to be photographed and subsequently circulated, this framework also undoubtedly defines and restricts what is deemed unsuitable to be photographed and published within mainstream media. Butler extends this, stating that:

We can even say that the political consciousness that moves the photographer to accept those restrictions and yield the compliant photograph is embedded in the frame itself. We do not have to have a caption or a narrative at work to understand that a political background is being explicitly formulated and renewed through the frame. In this sense, the frame takes part in the interpretation of the war compelled by the state; it is not just a visual image awaiting its interpretation; it is itself interpreting, actively, even forcibly (2005; 823).

Butler here is contesting Sontag’s belief that a photograph only frames and that it is in need of greater contextual information in order to read the image appropriately. The question behind these photographs must thus become who is operating the production of these images? That will enable us to comprehend the frame that may be imposed upon the photograph and the accompanying contextual use. Framing thus becomes the most vital application for the photographer, with a successful photographer being able to visualise the best frame for the situation or event, to elicit the strongest narrative and emotions. Which is why, as pointed out by Sontag (2003), many of the most poignant and iconic images of the century that seem to carry weight due to their visual significance have actually been staged by the photographer or subject. What becomes most surprising about these revelations is the sense of disappointment and shame from viewers who feel as though a photojournalist’s role is to capture truth and reality as it occurs, rather than creating a fabricated or dramatised interpretation of the event. This false expectation of an untainted truth or reality may actually be where the furore surrounding images of cruelty and torment originate. The expectations of photographic images appear to oscillate between two extremes (Didi-Huberman 2003). On the one hand, there is the expectation that photographs will provide an all-seeing sort of revelation about the ‘truth’ of the situation. Conversely, the expectation is that photography reveals nothing and only remains within ‘the sphere of the simulacrum’ (33).

Amid both expectations, the photographing of pain and suffering and the subsequent aestheticisation of these images become morally binding for viewers who hold these expectations of photojournalism. Can the ugly and disturbing truth of the event ever really be beautiful or breathtaking? Or is this imagery simply profiting on the pain and suffering of others by turning them into objects of visual pleasure? The exhibition entitled Beautiful Suffering, with a book published of the same, examined the key concepts and debates surrounding the aestheticisation and moral implications of images of suffering; and raised some thought provoking insights about the uses of this kind of photography as news information and other forms of commodities. Photography, it is contended, is bestowed with an almost blinding trust which:

Harbour[s] diverse illusions and excuses - for example, that the viewer need look no further to understand distant events; that structural violence requires only a personal emotional response; that the represented pain or calamity has already been resolved and can therefore be dismissed; or that addressing the problem is the privilege or the perquisite of the viewer (2007; 8).

The spectator is wholly implicit within the debate over graphic photojournalism. What is our role as spectators and how is our presence an implicit factor in the production and consumption of these images? More importantly, however, most of these images are taken of people and calamities abroad in ‘less developed’ parts of the world but are created by and circulated among mainly those within the privileged social sphere, in ‘developed’ societies. This may appear a generalization, yet in fact there is little to claim otherwise. Mainstream American media outlets are particularly guilty of parading distressing images when pertaining to countries and circumstances abroad and less keen to invite this imagery when it pertains to devastating events on their soil or to their people (Butler 2005; Sontag 2003).

Photographs of pain and suffering urge us to acknowledge what is happening within the frame. They beg us to relate viscerally and as humans to those in the images. They teach us of the suffering, pain and torment that are ‘out there’ in the world. They call to us to recognise the fragility of life and the inevitable truth of death (Sontag 1977; 2003). This relation of photography to death is a commonplace topic of discussion and for Barthes in particular. He believes that the spectrum, the person being photographed, treads upon the knowledge of their certain death. In describing having his picture taken, he states, ‘I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object: I then experience a micro-version of death (of parenthesis) : I am truly becoming a specter [sic]’ (2000; 14). Here the subject becomes a spectacle under the unremitting gaze of the spectator and in every picture the thought that looking into those eyes, the spectator holds the intimate knowledge that ‘you are going to die’ or even more chillingly ‘you have died’. Hence photographs of subjects pictured moments before death, such as the images of prisoners of the Khmer Rouge or those of Jews being round up in the Warsaw Ghettos, are ever the more poignant and disturbing. There is a vague sense that death is very near upon them and ever so present. Even if the subjects are truly unaware of their fate. There still appears a hint, amidst the fear and apprehension, of hope that the camera might be able to save their life; and if not in this one, then in the afterlife as a witness to the pain and suffering they have endured.

For the spectrum of the photograph, the camera and subsequent image produced becomes their unique testimony to the world. Even for those who may not openly consent to their image being taken, Azoulay (2008) insists that consent is implied within the terms of the civil contract of photography. Since the political space is free from state regulation, citizenship encompasses the global population of all those involved with photography at the level of: spectrum, spectator and operator. Hence she contends that for subjects within such photographs, inclusion in this community ‘offers an alternative [...] to the institutional structures that have abandoned and injured them’, and therefore ‘the consent of most photographed subjects to have their picture taken […] presumes the existence of a civil space in which photographers, photographed subjects, and spectators share a recognition that what they are witnessing is insufferable’ (18). This position raises questions as to the legitimacy of a so-called separate political space external to established sovereign state powers. In fact for many theorists, the photographic enterprise remains securely within the modes of normative production. Debord (1983) in particular maintains that the production of the spectacle is entirely contained by the means of production and reinforces class divisions. He argues that ‘the spectacle is the existing order’s uninterrupted discourse about itself, its laudatory monologue [...] the self-portrait of power in the epoch of its totalitarian management of the conditions of existence’ (8). Thus the images that saturate one’s consciousness may appear different on the surface, but are instead replicas of the system in which they inhabit. As consequence they tend to reflect the viewer back upon themselves rather than the subjects captured within the frame. This is an oversimplification of the fact that indeed photography can enlighten viewers and create a sense of urgency that may in fact help to formulate novel conceptions of the world around them. Conversely though, one cannot simply comply with the idea that photography transcends the frameworks and systems that create this injustice in the first place. Instead the contextual data surrounding the photographic event becomes essential to understanding its role, along with the possible beneficial and damaging outcomes it carries.

Part III

Photography is endowed with a sense of trust and an all-knowing truth that reappears throughout discussions about it, Sontag (1977) states that ‘photographs – and quotations – seem, because they are taken to be pieces of reality, more authentic than extended literary narratives’ (74). Didi-Huberman (2003) declares that photographs are indeed, borrowing Arendt’s term, ‘instances of truths’ (31). Benjamin (1972), fearing that photography would become an arena in which textual information would lose out, was concerned that without a context a photograph could be infinitely read and that interpretation would reign supreme over the verification of truth. In fact, this threat to the authenticity of photography, tearing it away from context would indeed reveal the limitlessness of photographs. The malleability of photographic readings becomes evident within the larger context of information. For example, the majority of photographs taken by photojournalists may never make the cut into news publications. The images that are left out not only create a more coherent narrative of the event, imposed or otherwise, but also illustrate the grander scheme of rich information that can help one draw out a larger understanding of the selective images published. The captions may differ when an image of a dead Taliban soldier is printed in a nationwide American newspaper, to the one that may accompany it in an art gallery or photo book. Hence the framing of photography is not limited to the selectivity of composition and subject matter. Photographs becomes further framed with the text that accompanies them, within the larger context which they are presented and also the ways in which they may be retouched or cropped for emphasis on particularities within the image itself.

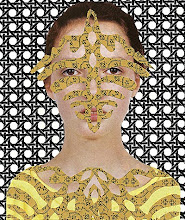

Photographs by the photojournalist and social documentarian Sebastião Salgado are stunningly beautiful and are regularly presented as images for visual pleasure through publication in coffee books or as exhibitions in art galleries. Conversely his images are renowned for their journalistic qualities of capturing social inequality, poverty and suffering. This grey area in which he occupies has given him a notorious status amongst critics who argue that his photography aestheticises pain and suffering rather than responsibly capturing the injustice. The argument materialises into a battle between the aesthetic and political realm, with the claim that they are mutually exclusive and that pain and suffering cannot be equally aesthetically appealing without jeopardising the struggle and demeaning the misery of those pictured. Salgado’s photo book Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age examines the physical toil and backbreaking labour of those in locations all across the world. His images are archetypal and are intended to reinstate dignity to the individuals pictured who he argues have become demeaned and exploited through the economic and social structures which keep them in their poverty. One of his most striking images in the book comes from the gold mines in Serra Pelada, Brazil and depicts the thousands of miners who work along the treacherously steep valleys (see plate 1). The people are indiscernibly human and look more like ants lined along an anthill. The subject in the foreground is a man resting with his back to the camera. His shirt is soaked through with mud and sweat. The folds in the shirt almost appear bronze-like akin to his skin tone. Upon first glance this image recalls an early iconic photograph of a slave’s back with uprooted scars from repeated lashings (see plate 2). The resemblance is striking. And even though the miner’s back is not scarred by whippings, it does not become unrealistic to believe that he may have similar scarring. What is most arresting about this image is the way in which Salgado has captured the slave-like labour he participates in and the slave-like repercussions he receives, without the need for any sensational jargon so-to-speak to grab our attention. In this sense the image does elicit a visceral response, one however that is more likely to entice viewers to seek beyond the image itself to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the situation. This should be the goal of all photojournalistic photography, to draw the viewer’s attention to the situation, but even further beyond what is pictured to the wider circumstances and politics that engender it. This weight on the image thus becomes shared between the contextual information that accompanies it: texts, discussions, other images, etc. With this in place, images without a context risk becoming simply objects of pleasure, spectacle and voyeuristic pursuits.

Plate 1 Plate 2

Sebastião Salgado. Gold miners of Serra Pelada, Brazil. 1993. Unknown. Scars of an escaped slave, US. 1863.

In his controversial documentary, Episode 3: Enjoy Poverty, Renzo Martens travels to the Democratic Republic of the Congo with one question ‘who owns poverty?’ Throughout his time in the Congo he meets international photojournalists making a living off of the images they capture of the conflict: raped women, malnourished children and the causalities of civil conflict. These photojournalists earn $50 per image and the photographs return to their international destinations never to be seen again in the Congo. Renzo attempts to help the Congolese take control of their poverty and gain access to the market by training local photographers to take images similar to those of the photojournalists. The images by the locals were subsequently rejected because they were deemed to be made with the intention of making money rather than making news. This emphasis on the intention or the merit of the photographer distorts the meaning of the image. How can an image solely be making news over another? Again, where is this threshold between sensationalist imagery and newsworthy imagery being drawn? This is precisely where one can witness the reproduction of modes of oppression within documentation; because what is considered documentation and newsworthy is restricted within the framework of the dominant power. Hence the limit is arbitrary and based solely on what is acceptable within the status quo.

A second pervasive issue raised by the film is that of the spectrum or the subject of the photographic gaze. Whist in the Congo, Martens visits a refugee camp alongside humanitarian workers who are providing aid and shelter to those displaced due to the civil conflict. The victims he witnesses become actors of poverty and take on the role of the helpless victim directly in front of the photojournalists’ lens and the humanitarian workers’ gaze. Their poverty is indeed a resource for them, but it also a resource for the NGOs and journalists. This co-dependent relationship is apparent in the obscene branding of the NGOs. With logos appearing on every item of aid, the question is, whose interests are the NGOs really serving? And it is here where photography of the pain and suffering of others becomes a mode of propaganda for both those in need and for the NGOs. For those suffering, the role they play in front of the camera dictates whether or not their plight will be recognized and supported. At the same time, for aid organisations, the visibility of their logos overseas is what ensures that they will be recognized and supported.

‘How do you make the unseen seen?’ (Peress cited in Linfield 2010; 258). Photography as a medium inherently makes something visible. The camera itself is endowed with the authority to show. If it is photographed then therefore it must be of some importance or value. The documentary Bus 174 reflects upon the ability of the camera to evoke a sense of importance, a sense of visibility and the troubling effects it has when it comes to representing violence through photography and video. The film recounts a day in Rio de Janeiro when a young man named Sandro hijacked a bus. Bus robberies are not uncommon among young people living on the streets as a means to get by, however, on this occasion, the robbery became a hijacking and a full-fledged media event. Photographers and news reporters flocked to the scene before the police and within minutes the event became broadcast live across the country. The event began in the afternoon and was over by dusk and resulted in the death of one passenger and Sandro himself. The culprit was a young man who became an orphan after his mother’s brutal murder and subsequently was forced to live on the streets. For most of the street children living in Rio and across Brazil their ‘greatest battle is against invisibility’.

This invisibility happens in two different ways: the child is invisible because his presence is ignored, he’s looked down on, or because we stigmatize him and only see a caricature. [And] when we project our prejudices onto someone, we cancel out and destroy what makes that person unique. We only see what we project onto him, a caricature, our own prejudices (Bus 174, 2002).

Thus for Sandro the presence of the multitude of video cameras and a vast audiences across the country was his moment of visibility. During this brief moment of notoriety, the camera had given him what society had never given him his entire life. The presence of the cameras throughout the event gave more power to Sandro, whilst paralysing the police’s actions (Hamburger 2008). Additionally, the presence of the camera elicited a role for Sandro to play that was almost expected of him. During the first hours of the incident Sandro is reluctant to be filmed and conceals himself from view. Eventually, he begins to take on the role of the victim-turned-villain brandishing his weapon and making threats directly into the camera and his act becomes increasingly dramatised as the afternoon unfolds. Thus the camera as a means of making him visible had rendered him a caricature of himself in which he was stuck. For Sandro, the cameras were his last shred of hope. ‘At the centre of this media event, Sandro enacted a reversed version of Foucault’s panopticon - he had the eyes of the world upon him’ (Hamburger 2008; 9). As long as the cameras were rolling, Sandro would remain alive and visible to everyone who watched. Shortly after his surrendered, he was hauled into a police van and under the supervision of no cameras. He was strangled and murdered.

Photographs of other people’s pain and suffering inherently carry with them a moral responsibility. Looking at a photograph of someone enduring the physical and mental distresses of war, famine or poverty is almost akin to a plea to be recognised and acknowledged; a cry to be heard, to be seen and to be saved. All photographs of such ask the viewer to take note of the atrocious event taking place, to remember the victims and to punish the perpetrators. These images call for us as viewers to look beyond the image and to ‘stop looking at the photograph and instead start watching it’ (Azoulay 2008; 14). Thus we must examine the image as a moment in time and space and part of a wider context. We must reflect anthropologically on the use and circumstances of specific images, and the intentions within the larger photographic enterprise (Didi-Huberman 2003). Where one draws the limit between sensationalist, pornographic photographs and those that are informative and empowering is ultimately arbitrary and again is a reflection of the image-maker and consumers’ ideological and normative frameworks. The market for images of pain and suffering will not die down. Wherever there is conflict there will be a photographer to document it. The only concrete thing these images can attest to is that human beings do indeed carry out atrocious acts of violence on fellow humans, and the endless stream of images only proves that it ceases to end.

References

Azoulay, A., 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. New York, NY: Zone Books.

Barthes, R., 2000. Camera Lucida. London: Vintage Books.

Benjamin, W., 1972. A Short History of Photography. Screen, 13(1), pp.5-26.

Bus 174. 2002. [DVD] Directed by José Padilha and Felipe Lacerda. Brazil: Zazen Produções.

Butler, J., 2005. Photography, War, Outrage. Modern Language Association: Theories and Methodologies, 120(3), pp.822-27.

Debord, G., 1983. Society of the Spectacle. Detroit, MI: Black & Red.

Didi-Huberman, G., 2003. Images in Spite of all: Four Photographs from Auschwitz. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Episode 3: Enjoy Poverty. 2009. [DVD] Directed by Renzo Martens. Netherlands.

Hamburger, E. I., 2008. Performance, Television and Film: Bus 174 as a Perverse Case of Appropriation of the Means of Constructing Spectacular Audiovisual Form. Observatorio Journal, 2(7), pp.1-11.

Linfield, S., 2010. The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Martens, R., 2011. Episode Three: Enjoy Poverty Q & A session. [discussion] (29 March 2011).

Price, M., 1994. The Photograph: A Strange, Confined Space. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

Reinhardt, M., Edwards, H., Duganne, E. Eds., 2007. Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Salgado, S., 1993. Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age. London: Phaidon.

Sontag, S., 1977. On Photography. London: Penguin.

Sontag, S., 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York, NY: Picador.

The Sarah Silverman Program. 2007. [DVD] New York: Comedy Central.

Friday, 13 January 2012

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment